- Home

- Zimmerman, Jacob

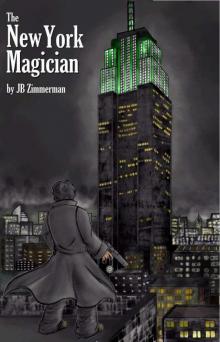

The New York Magician Page 4

The New York Magician Read online

Page 4

"Cher, listen to me." Her voice was thready but still had snap.

"Yes, Gran’mere."

"This thing I am doing."

"Dying, Gran."

"Yes, impertinent boy. Dying."

"What about it, Gran?"

She pushed the coverlet back a few inches and moved her hands about aimlessly before clasping them on her breast and looking at me. "It happens to us all, Michel."

"I know that, Gran." I was sitting in the chair next to her bed, trying not cry, trying not to hulk in my overcoat festooned with talismans of magic and firepower.

"No," she said, reaching out one hand to touch my forehead. I bent my head forward. "You think you know that. But you do not. I will die, Michel. It is something I fear. But that, too, is something that happens to us all, fearing death." Then she'd patted my cheek and gone to sleep again. I'd spoken to her three or four more times before she'd stopped waking up.

I waved at the bartender, who brought me another whisky. It burned, going down. This was worse than my parents dying. Much worse.

When they died, I had no Power at all.

My fist clenched against the vial again. It pulsed once, gently, in response. It could give life. That was its purpose. It could take my grandmother and lift her from her suffering, the suffering the doctors couldn't see; the pain from destroyed nerves that she was no longer able to express, her mind still present enough to feel but her spine long gone and even her muscles unable to grimace. The machines did not need to keep her alive, for she was breathing on her own, and that was the curse.

Every moment, she screamed, and no-one could hear her but I. But I could restore her.

She'd never spoken of it directly. There were no rules in this world where she played cards and fenced with the Immortals. There were no judges, no codes; just manners. Manners, she told me, were what would save me if I chose to swim in those waters. Not with humans, who cared nothing for such things, but with those to whom the things which humans cared about were less than nothing - with them, manners were all, and sacrosanct.

Manners had gained me the vial.

But somehow, I knew, without being told, that to use my gifted Power to bring her life would be discourteous. I had never risked being discourteous in the steps of the immortals before. I had no interest strong enough to risk discovering the penalty.

I did now, I thought. But I wasn't sure.

I didn't know if I cared.

I went back to the hospital, stared down at her lying in the bed, thought of coming to see her after using the vial to wake her up from her torment. In none of these conjurings could I see her with any expression other than a loving but sad disappointment.

She was still screaming.

I don't know how long I stood there. I don't know if I was crying. I know that at some point I snarled something wordless, pressed my right hand to my chest, and willed the world to change.

It did. The machines' lights faded to green. The screaming stopped.

I cried.

Later, I took the 6 train uptown to Grand Central Terminal and sat down before the bar at the Cafe. A soulless-looking supermodel stood before me without my hearing her approach, and placed her hands on the bar. I looked up at her, tears still tracking down my face, and squinted at the light streaming through the tall windows that framed her. "Baba?"

She touched my face. "You're crying." The voice might have been reading a financial headline.

"Baba, I need to return your gift." I drew the glass vial from the bandolier and placed it on the bar, staring at its crystal haze of refracting light for a moment. Clear liquid sloshed in it. I looked back up, but the supermodel had gone. In her place was a twisted crone with brightened eyes, eyes like my grandmothers' which caused fresh tears to slide down my cheeks.

"Why, Michel?" Her voice was cracked and aged, but her tone gentle.

"I used it, today. I used it-" I shook my head and pushed the vial to her. She picked it up, unstoppered it and waved it beneath her nose as though sampling perfume.

"Ah!" Her voice was surprised. She held it, looked at me. "Your grandmother. Your own baba. Is that why?"

"Yes." My voice was small. "I'm sorry, Baba."

"But why, Michel? That is what the Waters do."

I looked at her, confused. "I killed my grandmother, Baba. I used your gift to take an innocent life."

She laughed. "You are forgetting who I am, Michel." Her form rippled for a moment, straightening into a crone no less hideous but taller and terrible with fury. Her voice went cold again, the voice of the bitch queen supermodel. "I am Baba Yaga, little man; I am the mother of the Earth herself, and I have killed more innocents than you can begin to imagine have existed. I am death itself, and life; life when it is cruel, and death when it is a release." With that, her shape slumped again into the kindly bright-eyed woman, and she took the bottle and pressed it, open to my face, once on each cheek, so that two tears ran down into it. Then she stoppered it and shook it again, and the ripples in the fabric of the world flowed out from her hand. I stared at her.

"Michel, Michel. The Water of Death. What is it for? You know this answer."

I recited from memory. "The Water of Death is to allow corpses to decay, to free souls from their bodies so that-" I stopped.

She nodded. "So that the Water of Life may bring renewal from the ashes and the soul may rise to heaven. Did you use the Water of Life?"

"No, Baba."

Baba Yaga patted my cheek, exactly like gran’mere had. "And that is why you yet survive, Michel. You did not seek to grant her life. You simply chose to release her from pain, and to ensure her body went to rest. That is what the Water of Death is for. It was her time, and past her time; in those cases, that is when Baba Yaga is sometimes called to hasten what must be." She handed the bottle to me.

I took it, still staring at her. She patted my cheek again. "I will miss her, Michel. She was a worthy opponent. I am glad she sent her grandson to me to help pass the time."

"What would have happened if I had used the Water of Life?"

"Ah, but you did not. For that I am glad, Michel. It is a lonely life here, sometimes."

I don't know why I said it, but I did. "I've killed others, Baba."

"I know that, cher."

"I'm not a good man."

"That is not for you to decide." She turned and produced bottles, and without a flicker the supermodel bartender was in front of me mixing a White Russian, the light and the dark blending into my glass. I picked it up, tucking the vial into my bandolier, and raised it to her.

"Thank you, Baba. Please call on me if you have need." I sipped the drink, set it on the bar with a bill and turned to go, but a thought grasped me at that moment, cold and hard. Something Baba Yaga had said. I turned back to her. She raised one eyebrow, waiting. "Baba," I asked carefully, "How was my grandmother an opponent?"

She looked at me for a time. Then the ice queen bartender leaned forward and winked, one eye briefly brilliant with life and mischief. Then she stood, disinterested, and I gulped my drink and shuffled off downtown to begin a proper wake for the woman who had raised me.

VI

I want to reach my hand into the dark and feel what reaches back

* * *

The service was short and heartfelt. They laid my grandmother in the earth in quiet dignity, with a few words from a Catholic priest who had known her for longer than I had been alive and some murmured thoughts from her few friends. She'd outlived most of them. I stood at the end of the line afterwards, shook hands and endured the memories of all those old women intent on telling me what an adorable infant I'd been with a smile.

There were nine people at the grave besides myself and the priest, who shook my hand last and walked away to give me time and space for a family goodbye. I waited until he was out of sight around the trees before raising my head to the surrounding woods. "You can come out now."

Dozens of shapes, some nearly human and some entirely not, emer

ged from the shadows. Some walked. Some drifted. Some simply weren't and then were, a moment later. Those I had known were there but had been unable to point to came to the graveside with me to pay their respects to my grandmother.

I had had no idea how many of the New York dispossessed knew her. As I moved in their circles, toes dipping in the pools of myth and immortality, I had come to understand that she was a Power among them. Perhaps not one of control, or retribution, or of wealth; but a Power nonetheless, whose presence they would miss.

The tall, ice-faced woman knelt before the grave, quickly, and did something with her hands before standing and walking past me. She spared me one glance of her sapphire eyes, but they flickered once with the persona behind them, something rare and gifted only to me on this afternoon in our shared loss.

A nondescript man with a cellular telephone headset and Middle Eastern features came forward to look at the tombstone. I didn't recognize him, but when he turned to leave, he nodded to me, once, and was careful not to touch me. I bowed to him them, and when our eyes met again I placed my right hand to my breast and the hard shape there. He smiled once, pleased, and hurried off.

There were dark shapes near the ground that sniffed about her grave and then scurried away without looking back. A glowing form hovered over the open cut hole for a moment before floating upwards and out of sight despite a moment when I could have sworn that it was looking at me. And so it went, the gods and demons of New York paying, if not tribute, at least acknowledgement to the passing of a human who had known them.

When the last of them had gone and the graveyard was quiet, I shoveled earth thrice on the coffin and went home.

In my apartment, the same small one near the Hudson where she'd raised me, I looked at the desk in front of me and the objects arrayed there. A pocket watch, gold and white and ornate; a crystal vial, and a stone spear point. The three of them, free of their leather prison, represented the most powerful of the talismans I had collected in my years of negotiating and conversing with the powers of New York. Two of them I knew intimately. The third, the spear point of Bobbi-Bobbi, I had little idea how to use. My talent could feel the power in it, crackling, different from the smooth ripples of the vial or the glow of the watch, but I had had no luck in releasing it or bringing it forth by demand.

The doorbell chimed once. I rose wearily and went to answer it.

On the other side of the fisheye lens was the Middle Eastern man I'd seen at the funeral. I gaped for a moment, surprised, then turned the locks and opened the door. He looked up at me, having been examining the lintel. "You have protection here," he said in an unfamiliar accent.

"I do."

"That is good. May I come in?"

I looked at him carefully, then said "Please wait here a moment." He nodded. I closed the door and went back to my office, scooping up the talismans and placing them in my bandolier - save the pocket watch. With that in hand, I returned to the door. I opened it and opened my hand, the watch lying on my palm with the face up.

The man looked at it and smiled again. "Ah."

"Please pardon my caution. This is my home, and I haven’t seen this face. If you are who I think you are-"

"I understand." He reached out, very carefully, and touched the watch's face without touching me, then withdrew his hand. The watch gleamed brighter in the dim incandescents of the elevator lobby for a moment, then pulsed a deep and brilliant gold, light flooding from it to wash down the crevices and holes of the old building as the shadow inside it greeted its master.

I bowed and stood back to let the Djinn inside.

We sat facing each other across the scarred kitchen table where Nan and I had had our lessons those years ago. He removed the headset from his left ear and placed it deliberately on the table, pressing a button on it to still its bright blue blinking, before looking me in the eye. "What do you know of Irem Zhat al-Imad?" he asked me.

This wasn't what I had expected. "Irem of the Pillars?"

"Yes."

I frowned. "I've read of it. Please excuse my ignorance if this is incorrect. It was supposedly a city built in the Rhub al-Qali, the Empty Quarter of the Desert, by the Djinn. They built it at the behest of the lord of a giant race. It's a myth; no-one - that is, no mortal - has seen Irem."

The Djinn nodded. "Some of that is even true." He looked around my kitchen, then at his headset on the table. I had the sudden feeling he was trying to avoid continuing.

"Old One, do you have something to tell me?" I asked him quietly.

He looked up, the eyes in his vessel's head dripping orange flame down onto the floor. It hissed and vanished without harming anything. His face bore a rictus grin. "Yes, Michel. I need your help."

That was new. "If I can help you, Old One, I will." I looked into the silently flickering eyes as I said it, wondering idly if the man sitting across from me had a family and if so what they thought he was doing at the moment. Sitting in my kitchen discussing lost mythical cities probably wasn't it. "May I ask you to do something?"

"What?"

"If you have a story to tell me, I would ask you to visit me and release this man."

The Djinn slumped. The eyes faded back to normal. "That was my intention, if you would allow it."

I reached across the table and laid my hand palm up on its surface. "What shall I tell him?"

"He is a taxi driver. Tell him he has delivered his package to you and he will leave. His cab is parked downstairs." The Djinn didn't move for a moment. "It has been a very, very long time, Michel, since I had a body."

"What will serve you more at this time, a body or your power?"

"My power." He laid his hand on mine.

There was a flash of soundless noise, of dark light. I felt his fingers clench reflexively around my own for a moment, and then release. I opened my eyes from the squint they had assumed to see the man across my table look around, confused, and snatch up his headset. "Where am I? Who are you?" He stood, quickly.

I stood as well, digging in my pocket for a bill. I held it out to him. "Thanks for the delivery." He looked at me, face wild for a moment. I worked to hold my face pleasant and slightly curious, the five dollars extended. He looked around again, then took it automatically.

"Uh. You're welcome. Package ... ?"

"Yes. I'd hoped you'd get this to me within the hour, and all set, plenty of time. Thank you." I walked around the table towards the door. He followed, still looking around himself with a confused look but willing to be led. I nodded to him and ushered him out without touching him before locking the door and returning to the living room and seating myself on the sofa. There was a mirror on the wall opposite, a tall thin one that might have passed for decoration. I faced it.

"Old One?"

In the mirror, I nodded, my eyes glowing slightly. "Yes."

"Why don't you tell me what this is about?"

So I settled back onto my couch and listened to the tale.

* * *

The streets of Manhattan channel the flows of humanity, gutters of intellect and emotion on the feast of interaction that is urban life. Walking east towards Central Park from the 1/9 train I reached out with what senses I have and those I have stolen, but felt nothing out of the ordinary.

The Djinn's story has brought me here. He is gone, into a random commuter in the 14th Street Subway Station without a backwards glance, merely an assurance in my head that he will know to find me if I am successful. I reached a hand into my coat to touch the talismans for reassurance, feel their energy slick and warm near me. Bobbi-Bobbi's spearhead crackled strangely.

I passed the Museum of Natural History, settled in for the night in its small but comfortable block of parkland. The Planetarium building was a riot of glass and light on the north side, drawing my eye as I walked on towards Central Park.

The Park itself was dark, but not completely. Not the lethal anarchy of even ten years ago, Central Park now held strollers, the curious, the amorous, and even tourists. I sl

ipped into the interior, heading for the eastern side of the Reservoir, where the Djinn had said to look. Still nothing to feel, nothing to See or Hear.

But perhaps a half-kilometer short of my goal, all that changed.

I stopped short, there on the paved ribbon of the Park Drive, looking eastwards into the gloom. There was a presence there, some distance off but definitely in the direction I was heading. I'd never felt its like, but it was muted, somehow. A muffled basso drone of power.

I continued on, reaching the Reservoir, and circled it until I reached the closed and locked access point, iron door solidly shut in masonry stone. A maintenance access only.

The pocket watch flared, once, beneath my coat. There was a groaning shriek of metal and the door opened to let me slip inside and struggle to pull it shut. No-one noticed me inside my shield of ripples, the watch holding me invisible, but the sound might have gotten out. I hadn't thought of that. A few moments of waiting brought no response, however. I turned, pulled a mini Maglite from my coat, flicked it on and headed down the narrow steel stairs.

The pumping station wasn't quiet. I can't imagine it would ever be; its silence would imply New York's death, the water stopped. A constant moaning roar pervaded the space, which is lit somewhat indifferently. Gigantic shapes of piping, valves and locks huddle at the bottom of the space, much taller than a person, creating valleys and hummocks of shadow and steel. I let myself out of the access stairway and look around. There was an operator's booth visible down the gallery, some fifty meters distant, lit much more brightly than this sullen open space. I didn't see anyone in it, but if they're there, they wouldn't see me out here in the dimness. I stepped to the middle of the room and looked around myself at the pipes.

Then I Looked at them.

In my gaze, they changed. Sharply defined edges vanished; straight lines wavered. The ranks of industrial machined forms shimmered in my vision, settling into a row of gigantic squared stone shapes, no two alike, with the steel pipe visible at their heads and feet where it disappeared into the wall.

The New York Magician

The New York Magician